Mongo Santamaria

by Richard S. Ginell

A Mongo Santamaria concert is a mesmerizing spectacle for both eyes and ears, and even in his seventies, this seemingly ageless Cuban percussionist/bandleader could energize packed behemoth arenas such as the Hollywood Bowl. A master conguero, Santamaria at his best creates an incantatory spell rooted in Cuban religious rituals, quietly seating himself before his congas and soloing with total command over the rhythmic spaces between the beats while his band pumps out an endless vamp (a potent example on records is the hypnotic Mazacote available on Afro-Roots [Prestige]). He has been hugely influential as a leader, running durable bands that combine the traditional charanga with jazz-oriented brass, wind, and piano solos, featuring such future notables as Chick Corea and Hubert Laws. He also reached out into R&B, rock, and electric jazz at times in his long career. No Cuban percussionist, with the possible exception of Santanas Armando Peraza (and lets not count Desi Arnaz!), has reached more listeners than Mongo.

Ramon Mongo Santamaria originally took up the violin but then switched to drums before dropping out of school to become a professional musician. A performer at the Tropicana Club in Havana, Mongo traveled to Mexico City with a dance team in 1948 and then moved to New York City in 1950, where he made his American debut with Pérez Prado and spent six years trading percussive barrages with Tito Puente and performing and recording with Cal Tjader (1957-1960). Mongos first significant recordings in America were made in 1958 for Fantasy; his second Fantasy album, Mongo (1959), contained a composition called Afro-Blue, which quickly became a Latin jazz standard, taken up by John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and others.

Santamarias breakthrough into the mass market may have come as a result of a bad night at a Cuban nightclub in the Bronx in 1962. As the story goes, only three people showed up in the audience, so the musicians held a bull session in which the substitute pianist for the gig, Herbie Hancock, demonstrated his new blues tune, Watermelon Man. Everyone gradually joined in, the number became a part of Mongos repertoire, and when producer Orrin Keepnews heard it, he rushed the band into a studio and recorded a single that leaped to the number ten slot on the pop charts in 1963.

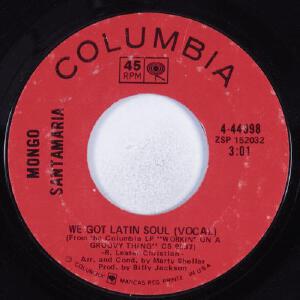

The success of Santamarias cross-pollination of jazz, R&B, and Latin music on Watermelon Man and a string of Battle and Riverside albums led to a high-profile contract with Columbia that resulted in a wave of hot, danceable albums between 1965 and 1970. With a brighter, brassy sound propelled by trumpeter Marty Shellers driving charts, often covering hits of the day, the Santamaria band perfectly reflected the mood of the go-go 60s, and Mongo continued to mix genres into the 70s. Santamaria then returned to his Afro-Cuban base, recording for Vaya in the early 70s, teaming with Gillespie and Toots Thielemans for a live gig at Montreux for Pablo in 1980, recording several albums for Concord Picante (1987-1990), a sole effort for Chesky in 1993 and a return to the Fantasy fold via its Milestone subsidiary in 1995. He died on February 1, 2003, at Baptist Hospital in Miami, following a stroke.

A Mongo Santamaria concert is a mesmerizing spectacle for both eyes and ears, and even in his seventies, this seemingly ageless Cuban percussionist/bandleader could energize packed behemoth arenas such as the Hollywood Bowl. A master conguero, Santamaria at his best creates an incantatory spell rooted in Cuban religious rituals, quietly seating himself before his congas and soloing with total command over the rhythmic spaces between the beats while his band pumps out an endless vamp (a potent example on records is the hypnotic Mazacote available on Afro-Roots [Prestige]). He has been hugely influential as a leader, running durable bands that combine the traditional charanga with jazz-oriented brass, wind, and piano solos, featuring such future notables as Chick Corea and Hubert Laws. He also reached out into R&B, rock, and electric jazz at times in his long career. No Cuban percussionist, with the possible exception of Santanas Armando Peraza (and lets not count Desi Arnaz!), has reached more listeners than Mongo.

Ramon Mongo Santamaria originally took up the violin but then switched to drums before dropping out of school to become a professional musician. A performer at the Tropicana Club in Havana, Mongo traveled to Mexico City with a dance team in 1948 and then moved to New York City in 1950, where he made his American debut with Pérez Prado and spent six years trading percussive barrages with Tito Puente and performing and recording with Cal Tjader (1957-1960). Mongos first significant recordings in America were made in 1958 for Fantasy; his second Fantasy album, Mongo (1959), contained a composition called Afro-Blue, which quickly became a Latin jazz standard, taken up by John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, and others.

Santamarias breakthrough into the mass market may have come as a result of a bad night at a Cuban nightclub in the Bronx in 1962. As the story goes, only three people showed up in the audience, so the musicians held a bull session in which the substitute pianist for the gig, Herbie Hancock, demonstrated his new blues tune, Watermelon Man. Everyone gradually joined in, the number became a part of Mongos repertoire, and when producer Orrin Keepnews heard it, he rushed the band into a studio and recorded a single that leaped to the number ten slot on the pop charts in 1963.

The success of Santamarias cross-pollination of jazz, R&B, and Latin music on Watermelon Man and a string of Battle and Riverside albums led to a high-profile contract with Columbia that resulted in a wave of hot, danceable albums between 1965 and 1970. With a brighter, brassy sound propelled by trumpeter Marty Shellers driving charts, often covering hits of the day, the Santamaria band perfectly reflected the mood of the go-go 60s, and Mongo continued to mix genres into the 70s. Santamaria then returned to his Afro-Cuban base, recording for Vaya in the early 70s, teaming with Gillespie and Toots Thielemans for a live gig at Montreux for Pablo in 1980, recording several albums for Concord Picante (1987-1990), a sole effort for Chesky in 1993 and a return to the Fantasy fold via its Milestone subsidiary in 1995. He died on February 1, 2003, at Baptist Hospital in Miami, following a stroke.

单曲